Sometimes, one of the very hardest things about growing up is finally seeing your parents for who they really are. Sometimes, that process just happens to intersect with another hard part of growing up: falling in love for the first time.

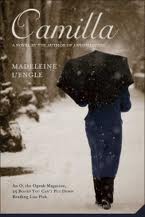

Camilla was Madeleine L’Engle’s fourth novel and third work for young adults. Published in 1951, and set in the late 1940s, it tells a painful and joyful tale of three weeks in the life of Camilla Dickinson, a wealthy New York City teenager, and represents a major shift in focus and tone from her previous book, And Both Were Young.

Camilla has spent her life sheltered by her parents, who employ at least two servants and several governesses in the austere war and post-war era. Only recently has she been allowed to go to school and been able to find a friend, Luisa. (Or, more strictly speaking, had Luisa find her: Camilla is shy and often inarticulate, and Luisa initiates that friendship.) Just as she is beginning to discover herself and her world (as defined by New York City), she returns home to find her mother, Rose, in the arms of a man who is not her husband. This is a shock; Camilla has, until now, believed her family was happy. (As it turns out, she believes this in part since she has chosen not to think about some earlier, less happy childhood memories.) The situation only worsens when her mother asks her to lie, and her father asks her to spy, and when Rose, the overdramatic sort, caught between her husband and her lover, makes a suicide attempt.

In the middle of this, Camilla does find one saving joy: she finds a new friend, and more surprisingly, she falls in love, with her best friend’s brother, Frank.

The love story between Camilla and Frank, brother of her friend Luisa, is presented painfully and unflinchingly. Frank, like Camilla, is dealing with his own emotional troubles—he has just lost his best friend to a gun accident and gotten himself kicked out of school. And he and Luisa have their own parental problems: their mother is an alcoholic, facing another marriage that is falling apart. (Those still convinced that contemporary divorce rates and marital problems began in the 1960s with the women’s rights movement should certainly take a look at this book.)

But Camilla does not fall in love with Frank simply because of his troubled family, but because, to her joy, she has finally found a person that she can really and truly talk to, about everything: not just her family (she remains somewhat reticent on this, even with Frank, finding it too painful to discuss), but astronomy and music and God. And Frank leads her to another friend, a wounded veteran named David who lost his legs, who turns out to be another person Camilla can speak with. This leads in turn to some marvelous conversations, full of angst and speculation about stars and wonder and despair and God fear and truth and hope. Something Camilla terribly needs.

Camilla’s parents are, to put it mildly, awful; perhaps the nastiest scene is one where they turn on her, accusing her of insensitivity and thoughtlessness. In a rather spectacular feat of self-delusion, the parents blame Camilla’s changed behavior on her friends Luisa and Frank, instead of their own actions, and decide to send Camilla to a boarding school without consulting her. About the only one of the three adults who acts with any consideration for Camilla is, surprisingly, Rose’s boyfriend; unfortunately, he’s the sort of well meaning person who thinks it’s appropriate to give elaborate dolls to 15 year olds, and his attempts backfire, upsetting Camilla even more.

Since the book is told in the first person, and Camilla tells these stories unflinchingly: it’s hard to know, at times, if she’s aware of just how horrible they are. One conversation with her father does lead to her throwing up in a bathroom, but otherwise, as Luisa notes, Camilla has not learned to see her parents clearly. Even her realization that she hates her mother does not lead to the realization that she is angry at her mother for what her mother is doing to her.

Nor can she do much more than verbally protest, and sometimes, not even that. Camilla manages a few minor rebellions—staying out late a few nights, refusing to answer some of her parents’ questions, but when her mother announces that Camilla is going to boarding school, Camilla knows she has no choice. Her friends, too, can speak, but little else: a significant part of this book involves learning to handle things that you cannot change.

Part of the problem, often left unspoken, is World War II, lingering in the background. David and his mother may be the only two characters to be obviously physically and emotionally wounded by the war, but others still show signs of fear, resignation and doubt. Most characters seem to agree, for instance, that a third world war is coming, and they can do nothing about it.

The Christian faith that would become such a central theme of L’Engle’s later books makes an early appearance here on a decidedly tenuous note. Camilla voices a faith that will later be echoed by other L’Engle characters, but sounds doubtful about it. Frank wants an entirely new religion and an entirely new god in the post war era. Many of their conversations sound like internal debates, perhaps sparked by L’Engle’s own early explorations of faith, decidedly tested by the horrors of war. In later books, L’Engle’s characters would doubt, and even experience moments of lost faith, but their narrator would not.

One interesting note: in this 1951 book, Frank and Luisa’s mother holds a full time professional job and is the family breadwinner, and both Camilla and Luisa assume that they will be heading into professional and scientific jobs as an astronomer and doctor/psychiatrist respectively. This, too, began a theme that would be repeated in later books, as L’Engle featured professional women, including pianists, Nobel prize winning scientists, gifted doctors and more in future works.

Also interesting: none of these women would call themselves trailblazers, even though in the earlier books, at least the Nobel prize winner might have been called so. They simply take their professions for granted, as do their peers. One or two—primarily Dr. Murry in A Wrinkle in Time—face slight hostility or befuddlement from the community, but for the most part, this is not because they are working, but because they are working extraordinary jobs. I suspect the matter-of-fact tone here stems from L’Engle’s own self-awareness as a working professional, but it’s a refreshing reminder that women did not suddenly enter the professional workplace in the 1970s.

With all this, Camilla undoubtedly sounds like a very depressing book, and in some ways it is. But in other ways, it is an equally joyful book, as Camilla learns what friendship is, how to handle pain, and what adulthood is. (That last is less painful than it sounds.) And if this book doesn’t have a hint of speculative fiction in it—except perhaps for the conversations about stars and the moons of Saturn—I think it works for geeks, largely because we’ve all been there, wanting desperately to find someone, anyone, who speaks our language. And anyone who has lived through the fallout of a broken or cracked marriage can find considerable comfort and understanding in Camilla’s story.

L’Engle liked the characters of this book enough to bring them back for cameo appearances in other books and in a sequel published 45 years later, A Live Coal In the Sea, distinctly written for adults, but featuring the same painful emotions.

Mari Ness has been occasionally known to get off track with conversations about moons, typically ones yet undiscovered around yet unvisited stars. She lives in central Florida.